| Home | About the OAC | Capitol Complex | Recent Projects | Master Plan | Public Meeting Notice | Contact Us |

| History of the Illinois State Capitol |

|

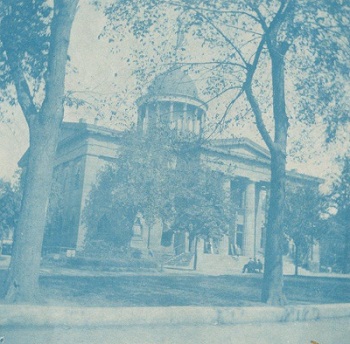

In the thirty years between laying the cornerstone for the first state capitol in Springfield, July 4, 1837, and the meeting of the Twenty-fifth General Assembly in 1867,

the population of Illinois mushroomed from one-half to two and one-half million people. The old capitol on the square, itself not completed until 1853, was woefully inadequate to contain the needs of a post-Civil War industrial state. Knowing that Kaskaskia and Vandalia had previously lost the honor and benefits of being Illinois' capital, former Springfield Mayor James C. Conkling campaigned for state representative in 1866 and easily won on a platform to build a new state house in Springfield. Despite grand offers from Decatur and other cities to be the capital, Conkling's bill quickly became law. |

|

|

Legislation "to provide for the erection of a new state house" was signed by Governor Richard Oglesby February 25, 1867. This act outlined the procedure whereby

Sangamon County and Springfield would purchase the old capitol while giving the state almost nine acres of property that two years earlier had nearly been the site

of Abraham Lincoln's tomb. In addition, this act named seven men to a state house commission, which was responsible for overseeing the planning and construction of the capitol.

In July the plan submitted by Chicago architect John Crombie Cochrane was selected from twenty-one designs received in a national competition. Cochrane was awarded the $3000 premium, and in January 1868 he was also appointed capitol architect and construction superintendent. His firm's commission was set at two and one-half percent of all construction costs. On February 5, Cochrane formed a partnership with Alfred H. Piquenard, a Frenchman who in 1848 had immigrated to the United States. Piquenard moved to Springfield in 1870 and directly supervised the construction until his untimely death November 19, 1876. |

|

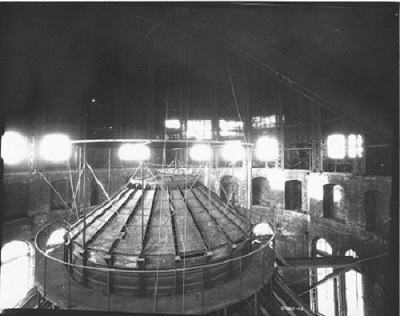

Ground was broken on March 11, 1868, when Capitol Commission President Jacob Bunn plowed a furrow half-way around the foundation line and Commissioner John W. Smith

completed the task. During that summer the foundations were put in place. The circular foundation upon which the great dome rests is ninety-two and one-half feet in diameter. Its seventeen-foot-thick magnesium limestone walls are based on solid rock twenty-five and one-half feet below grade line. The foundation for the other walls varies from eleven to sixteen feet below grade line, with the walls nine feet thick up to the first floor. |

|

Before any construction started, a railroad spur was run down Monroe Street from the Toledo, Wabash, and Western Railway near Tenth Street to the capitol grounds. The rail line encircled the construction site and made it easier to deposit heavy loads close to the construction site. Several wooden derricks were used to lift the limestone blocks to all locations on the building. A large celebration was held October 5, 1868, for the official laying of the engraved cornerstone. Jerome R. Gorin, grand master of Illinois Masons, |

|

|

presided over the ceremonies and anointed the eight-foot-long stone with "the Corn of Nourishment, the Wine or Refreshment, and the Oil of Joy." Prayers were said to the "All-bounteous

Author of Nature," and His assistance was requested to complete the building, protect the workmen against accident, and long preserve the structure from decay. The stone was then ritualistically tested with the plumb, level, and square and found "tried, true and trusty." Ironically, two years later several large cracks in the stone forced its quiet removal and replacement by a plain stone. The original cornerstone was buried in November 1870 without ceremony, and people eventually forgot its location. The stone remained "lost" until July 1944, when it was unearthed under the east stairs and placed at the north corner of the east entrance, where it rests today. |

|

Worries about rising construction costs, concerns about poor building techniques and materials, and continual political jealousies prompted several legislative

investigations. In the spring of 1869 a review by construction experts resulted in the following changes: The commission was reduced from seven to three members;

the use of iron, wood, and plain stone was substituted for marble on the interior; all limestone for the outer walls was to be cut and prepared by convicts in Joliet;

and, most importantly, the new state constitution of 1870 put a $3.5 million limit on costs. Any amount above this would require approval by a majority of voters in

a direct election.

Also, many people again urged that the capital be moved to Springfield. Peoria hosted members of the legislature in early 1871 and made a munificent bid for the transfer of the capital to that city. Likewise, Chicago invited the General Assembly to hold its fall session there in November, offering the state suitable assembly halls and executive and committee rooms free of charge. This offer was accepted despite the constitutional provision that all sessions of the General Assembly be held in the capitol. Were it not for the Great Fire of October 8 and 9, Chicago might have become our fourth state capital. Construction crept along in Springfield under the direction of Piquenard, who at the same time was building Iowa's capitol. When he died in November 1876, the building was still not finished. However, the General Assembly began its first session in the new building January 3, 1877. |

|

The main entrance at this time was on the east side and was reached by thirty-seven outside steps leading to the governor's office on what is today called the "second" floor.

In 1877 this was considered the principal floor because it contained the executive offices, law library, and supreme court. Today's first floor was considered the basement and consisted mainly of rooms for minor officials and storage. The interior of the dome and rotunda were unfinished, and walls and ceilings throughout were drab and not yet decorated. |

|

| Construction now was halted as all appropriations had been spent. Experts testified at legislative hearings that an additional $531,712 was needed to complete the work. A request for this sum was submitted to the state electorate in November 1877 but was soundly defeated. It was defeated again in 1882, but in 1884 it was confirmed by a majority of the voters. |

|

Under the direction of newly elected Governor Richard Oglesby, the man who began the project when previously governor in 1868, new commissioners were appointed, enabling

legislation was passed, and architect W.W. Boyington, designer of the Chicago Water Tower, took over the construction project and saw it through to completion.

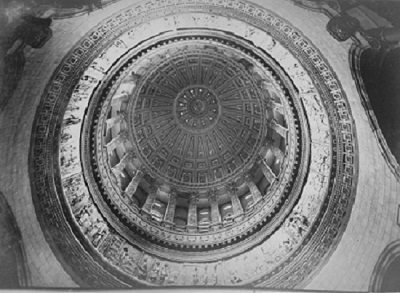

Starting in October 1885, the outside east entrance steps were removed, and entrances to the new "first floor" were installed under columned porticos on the east and north sides. Finishing touches included marble wainscoting and floors, historical murals, allegorical paintings, political statuary, decorative plastering, and a stained glass oculus in the inner dome that depicted the state seal. |

|

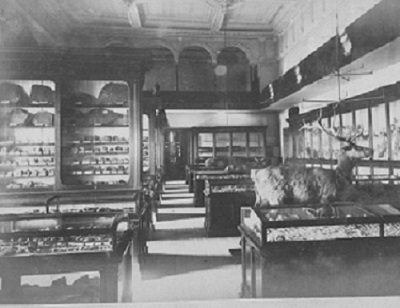

The building was reopened to the public on January 1, 1887, as 144 gas jets illuminated the dome decorations while other lights above the stained glass allowed people to see

clearly the state seal. By the summer of 1888, $4.5 million had been spent to construct and repair a building that was crowned by an exterior dome seventy-four feet

taller than that of the United States Capitol. Three elevators operated in the rotunda, telephones were installed in the major offices, typewriters were common, and within

a decade electric lights replaced the gas fixtures in halls and offices. The public was given an government building that contained all constitutional officers, legislators,

supreme court judges, clerks, government departments, regulatory boards, military leaders, as well as three museums, several libraries, and the state's archives.

On July 11, 1888, after twenty-one years of effort, the final construction bills were paid, and the state house commissioners returned the remaining balance of $6.35 to

the state treasurer.

|

|

• Suite 602 Stratton Building • Springfield, Illinois 62706 |